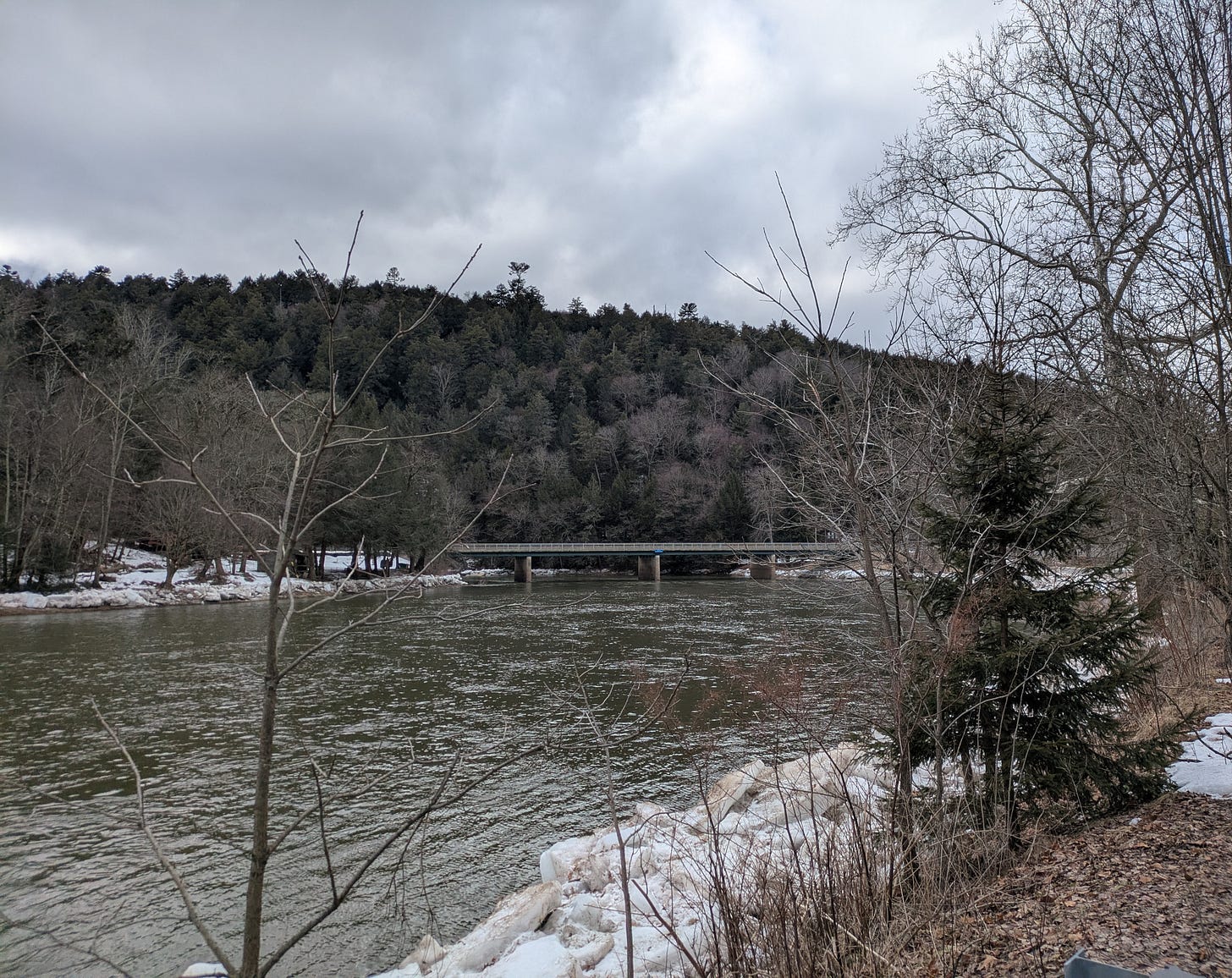

As February transitioned into March, I was nestled in a cabin along the Clarion River in Cook Forest. Its water was at its highest point, over six feet deep, as the ice and snow in the mountains began to melt away in preparation for Spring.

During an early-morning excursion to spot river otters, a ranger shared history with us: this is the time of year local loggers would create a huge raft out of felled trees and ride it to the Allegheny River. They’d travel all the way down to Pittsburgh on these stacks of logs, 8 feet tall and as long as they could manage. They’d sell the trees they just floated on and then hike the 100 miles north back home. Apparently, someone once fell off the raft and died trapped under the huge floating bundle.

I felt that this was an adventure I would be cut out for.

While hiking in Cook Forest, I communed with old-growth Eastern Hemlock trees. This region is home to much of what remains of old-growth Hemlocks, with at least one over 470 years old.1 I thought about how these Elder trees existed long before the industrialization period of the United States. They witnessed and survived the complete transformation of their region.

Western Pennsylvania was the heart of the industrial revolution. When I’m in these forests, I can feel it. Generations of labor, sweat, and sacrifice went into this land so that the resources here could be alchemized into the future of a nation, in cities far away. There is pride here, but also pain. Not all subscribed to what was being imagined. Many simply needed to keep their families fed and their houses warm, feeling no choice but to bend to the will of a system they had little control over.

I know that my history resides in forests such as these but I lack knowledge of specific stories. I mourn for those exploited, feeling personally the lack of generational security given to the people closest to the land. The infrastructure here was built on extraction, and then abandoned.

The trees hold their own history. They stood silently while thousands were floated down river, their fates bound with a churning city.

Many of the forests in North American were devastated by logging and deforestation in the late 1800s, the time of the industrial revolution. In some regions, “attempts to convert the forest to agriculture failed, and by 1950 fire control and forest conservation efforts began the slow process of reforestation.”2 Reforestation has proven to be challenging, as seeds were lost in the fires and over-population of white tailed deer make it hard for young trees to thrive.

Today, Eastern Hemlocks are considered “Near Threatened” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, but are “Apparently Secure” from extinction. Current threats come from the hemlock woolly adelgid, an invasive bug that was introduced to the United States in 1924 from nursery plants imported from Japan.345 Many of the oldest trees in the forest have been lost to the adelgid.

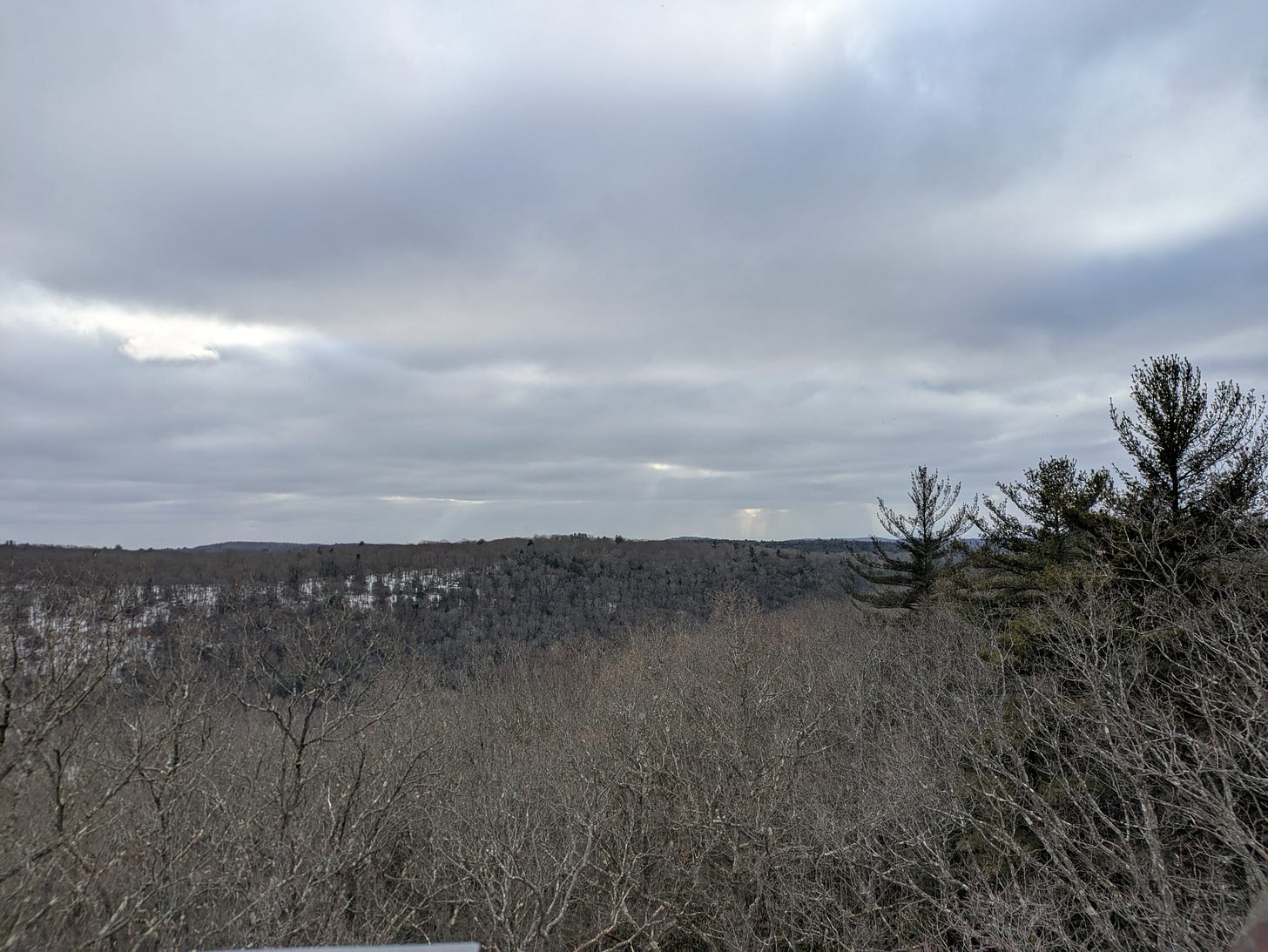

Stationed amongst the Eastern Hemlocks in Cook Forest is Old Fire Tower #9, completed on August 18, 1929, a year after Cook Forest was formally established as a natural preservation area. “It stands 87.5ft tall,” the placard next to the tower reads, “and has withstood many windstorms over the years. It is one of the very few remaining original fire towers in the state that permits public access.”

The tower was initially built as a tourist attraction and wasn’t used as a fire tower until 1948. “Paid forest fire observers manned the tower for 8-hour days during the yearly fire season until 1967 when a tornado blew down its electric and phone lines. The tower has since reverted to its original use.”

The box at the top of the tower is closed, but the rest of the tower is accessible. Despite my fear of heights, I followed my friends as we climbed up to the highest platform. I yelled out in fear when the wind shook the structure, crouching low, too afraid to stand up all the way. At the top of the tower, I gripped the rails and watched sunlight stream through cracks in the clouds. On the way down, I paused just long enough for E and I to take photos of each other.

After climbing back down I turned to the group and shouted, “Did you see how brave I was?”

Back in the cabin, nine of us cozied up by the hearth, played games, and watched bad movies. Winter was still very much with us, held with the anticipation of Spring around the corner. It was a weekend of connection and stepping out of the discordance of the working world. It helped make everything feel a little more bearable when we went back home.

I brought back with me some Eastern Hemlock branches I foraged during our hikes - bright green pieces I found on the ground, already detached from their mother tree. Their needles sit on my altar to invite the wisdom of the trees into my home.

Although my knowledge of history is limited, I feel the rumbling soul of the land, the way it holds its own memory. I think about the Eastern Hemlocks and am comforted by how much they’ve already seen. They remain calm and patient in the face of change. Human concepts such as nation and authority do not worry the Hemlocks, and this soothes me. In 100 years we will be gone, but the Hemlocks will remain, holding the stories they’ve witnessed along the way.

Learn more about the recent decline of the Eastern Hemlock at The Gymnosperm Database

"Human concepts such as nation and authority do not worry the Hemlocks, and this soothes me." Me, too.